Grief, Bereavement, and Chronic Pain

Exploring the relationship between losing someone and chronic pain has been important to me ever since I discovered Clinical Somatic Education (CSE). Both for my clients, and for myself.

Two things became crystal clear to me when I learned about CSE: first, it was after my Dad’s unexpected, sudden death that my minor aches and pains transformed into what’s labelled ‘chronic pain’. Second, from my experience as a bereavement counsellor, I knew that losing someone close often becomes a tipping point – suddenly there’s a flood of new symptoms, because the hard work of holding everything together becomes too much.

It made perfect sense. When you’re already carrying stress in your body, adding the enormous weight of grief – often experienced as trauma, and always as stressful – can push you over the edge.

What I See in My Practice

As a Certified Clinical Somatic Educator, I’ve watched many clients experience grief’s lasting effects on their body. Sometimes they make the connection themselves between their loss and their physical symptoms. More often, they don’t.

Grief, bereavement, and loss are incredibly heavy loads to carry. The stress hits your entire soma – your whole embodied self – whether it shows up as physical pain or emotional overwhelm. And when loss is sudden? It’s often traumatic, too.

How Grief Gets Stuck in Your Body

Your body already holds patterns of tension and tightness from previous stresses. When you experience the shock and trauma of profound loss, those existing patterns don’t just continue – they intensify. Your nervous system doubles down on what it already knows how to do.

And if neuromuscular tension is already a big part of that knowing? Then that’s part of the response.

So, if your usual response to stress shows up most often as tight shoulders and a clenched jaw, that’s most likely what will happen when grief hits. Your brain and neuromuscular system fall back on familiar patterns, layering new tension on top of old.

This is why there’s a pretty much inevitable link between loss and chronic pain – especially for those of us who held stuck stress in our neuromuscular and nervous system to start with.

Chronic Pain

When I talk about chronic pain, it’s important to realise I don’t just mean official diagnoses and conditions that use that term. I’m talking about any pain – including stiffness, discomfort, and soreness – that lingers more than 3–6 months after tissue damage has healed, or any pain without a clear medical explanation.

So if you’re dealing with persistent back pain, tense shoulders, sciatica, or other pain you just can’t shake, you’re likely experiencing chronic pain. And most chronic pain has neuromuscular roots. (Access my free resource about this here.)

The Stress—Pain Connection

Neuromuscular pain is directly related to stress. This is the foundation of Thomas Hanna’s work, of his Clinical Somatic Education, and of all my client work.

When stress causes you to lose touch with how to sense yourself fully, you forget how to move naturally. This creates even more stress, which then gets stuck in your body. It’s a vicious cycle.

For most of us, grief pulls you away from yourself. You become distracted, less able to pay attention to your own needs and sensations.

So grief isn’t just its own form of stress – it’s all that plus an amplification of any patterns of tension already held in your neuromuscular and nervous system.

It’s really, really hard.

Different Ways We Respond to Grief

People respond to grief in different ways, and each response creates its own physical patterns:

Some people go into overdrive – the ‘fight’ response. They might throw themselves into practical tasks like funeral arrangements, or run from their feelings by staying frantically busy with everything else.

Others want to turn away from it all. This often gets labelled as ‘denial’, and I see it as the ‘flight’ response in action – wanting to flee from the reality of what’s happened. (There’s some overlap here, too, with getting caught up in practical arrangements: those have to be done, yes, but doing them can be flight as well as fight, depending on each individual’s response.)

Still others collapse and shut down. This might look like depression, exhaustion, physical lethargy, or all of the above. This is akin to the collapse response – the ‘playing dead’ that is the last resort of a nervous system that feels like it has no other choice.

Most of us cycle through aspects of all these responses, and our patterns can shift over time.

But what’s important to recognise is that the physical patterns from each response – especially from that initial shock of your loss – can persist long after the acute grief has passed.

Those patterns get stuck in us.

The Lasting Impact

For some people, this might mean experiencing unpleasant physical symptoms for a short time after their loss. But for others – especially those who already carry stuck stress and ongoing physical discomfort – grief can trigger a flare-up of existing symptoms or lead to a worsening that persists well after the initial shock has faded.

Understanding this connection between grief and chronic pain isn’t just academic – it’s the first step toward healing both.

The Literature

There’s surprisingly little written about the link between chronic pain and grief, even though, as José Antonio Garciandía Imaz and Claudia Marcela Rozo Reyes note, it’s so often ‘mentioned intuitively as a condition taken for granted’.*

Putting chronic pain into existential context, we do know that it is often a ‘wake-up call’ about chronic suffering, and that that suffering is often hidden from the person experiencing the pain.

With grief, it would make more sense that someone knows the cause of their pain, we might think? They know they lost someone, and they know it hurt.

However, it seems to me that even when we acknowledge the loss of someone as painful, we maybe don’t recognise just how painful it is – and how it impacts on our whole life, our whole being. That might be another, related reason that prior discomfort and pain might worsen after a bereavement – if it’s signalling that there’s more to be done, more to be acknowledged.

The Grief–Chronic Pain Connection: what do we know?

Here, it might make sense to quote some of what Garciandía Imaz and Rozo Reyes found from reviewing research in the field, having established that ‘the information available shows a neurobiological connection between chronic pain and grief… they share some neurological locations and some neuronal circuits’ (189).

They note that:

‘Grief and chronic pain are related on a symbolic level to speech; both concepts have a common etymological origin [this is especially clear in Spanish, the authors’ first language]’;

‘Chronic pain is a body expression of the difficulties of a person to renew their existence in the face of the loss of a beloved object or another significant aspect of their life’;

‘Chronic pain and grief share psychological aspects in their process and evolution… In both cases, the individual is involved in the process of relearning the world and readaptation to a situation that exceeds their current processing ability’;

‘… unresolved grief is expressed in somatic pain which becomes chronic’;

‘Chronic pain, as a generator of disability, results in the production of grief, and unresolved grief results in somatisation, of which the most common is chronic pain’ (189).

The Grief–Chronic Pain Connection: what do we feel?

It’s interesting and important to acknowledge that similar areas of the brain deal with grief and with pain, as too is the common root of ‘grief’ and ‘pain’ in linguistic expression.

This goes to substantiate what so many of us might feel, viscerally and intuitively, about the connections between grief and chronic pain. It also makes more sense of my own experiences, and those of my clients, whose physical pain has worsened – or arisen – following the death of a loved one, experienced as inevitably stressful, and often as a trauma.

There’s another interesting component to all of this: an existential one. The idea that chronic pain from bereavement, and perhaps more widely, comes from a lack of resolution, a lack of completeness, in your life. (Hence, unresolved grief, or unresolved issues in one’s life, cause literal discomfort).

This accords with my experience as a CCSE and an SEP, but it’s still an area lacking clarity and worth considering from an individual perspective.

Plus, we don’t want to over-simplify the experience.

Chronic pain after a bereavement is not simply ‘unresolved grief’, in my view. It is more complex than that. It arises always in a fuller somatic–existential context of how stress and trauma are already processed or stuck in each individual soma, and how we respond to that stuck-ness – and whether we have been given the tools to do so (such as Clinical Somatics, SE work, or whatever).

Change is always possible. ‘Resolution’ of grief, of pain, is perhaps always possible too.

But grief, like our stress-response patterns embedded in our neural pathways, can never be deleted.

It can only be overwritten with new experiences, new responses.

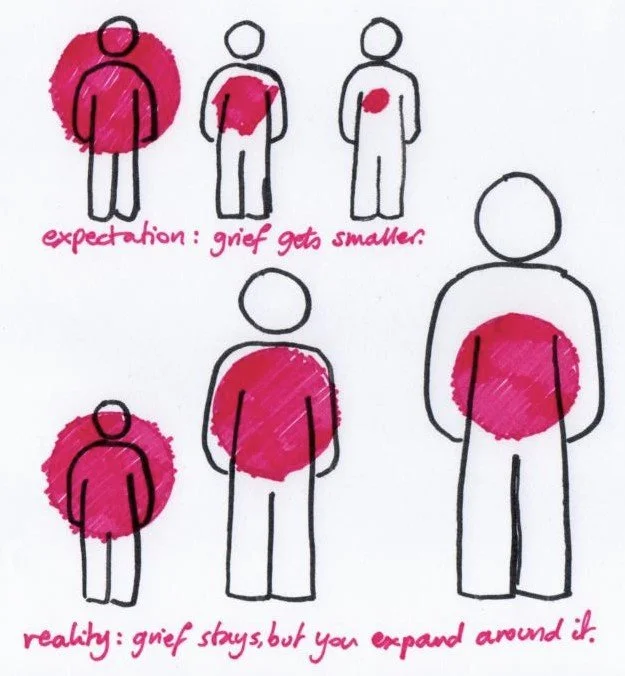

In this sense, the model of bereavement that shows us ‘growing around grief’ is useful, I think, in considering how we might relate to chronic pain.

The diagram below is my interpretation of Tonkin’s model of grief (by far the most useful model I found for myself and for clients); it shows that while we tend to expect grief to get smaller over time, that’s not what happens. The grief – our loss, our bereavement – does not diminish over time. But our life grows and expands around it, providing a bigger container for it, so that it feels less huge, less all-encompassing, over time.

Experiences of chronic pain, like experiences of grief, will always be with us.

But we can always expand around them, and make our lives more full, and less bogged down by unhelpful patterns and habits. (We can do this by rewiring our brains into more beneficial, more flexible patterns; that’s what CSE does.)

And we can do all of this without forgetting those we grieve, and without denying facets of who we are and all we have been.

* They continue: ‘However, little evidence of this relationship has been published, which suggests that this topic has not been widely researched’: José Antonio Garciandía Imaz and Claudia Marcela Rozo Reyes, ‘Chronic pain and grief’, review article, Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019 48(3): 182–191